Supporting the overarching principle of not accidentally pulling readers out of our story, today’s blog is about data dumps. This was another lesson from summer workshop, but also a principle I learned while writing my memoir. Sometimes in fiction and memoir it’s hard to figure out how to give readers background story or provide context as to what’s going on without pulling them out of an active scene. If we spend too long in explanation, which interrupts action, it’s called a data dump, or information overload.

Once in a while we might need a little background to illuminate why a character is behaving the way she is. Or maybe we’re writing science fiction and using otherworldly terms which require orienting the reader or cluing him in. One device is to use an active flashback scene, but many times background story or explanation isn’t enough to merit a separate scene. And we can’t cheat and do it clumsily in dialog, either, because characters would never sit around telling each other what they already know.

It’s so easy for our eyes to slide past information-packed paragraphs written in a neutral, journalistic tone. After a point, we start wondering when we’ll get back to the main story, back to the conflicts and problems and emotions. So how do we approach explanatory narrative?

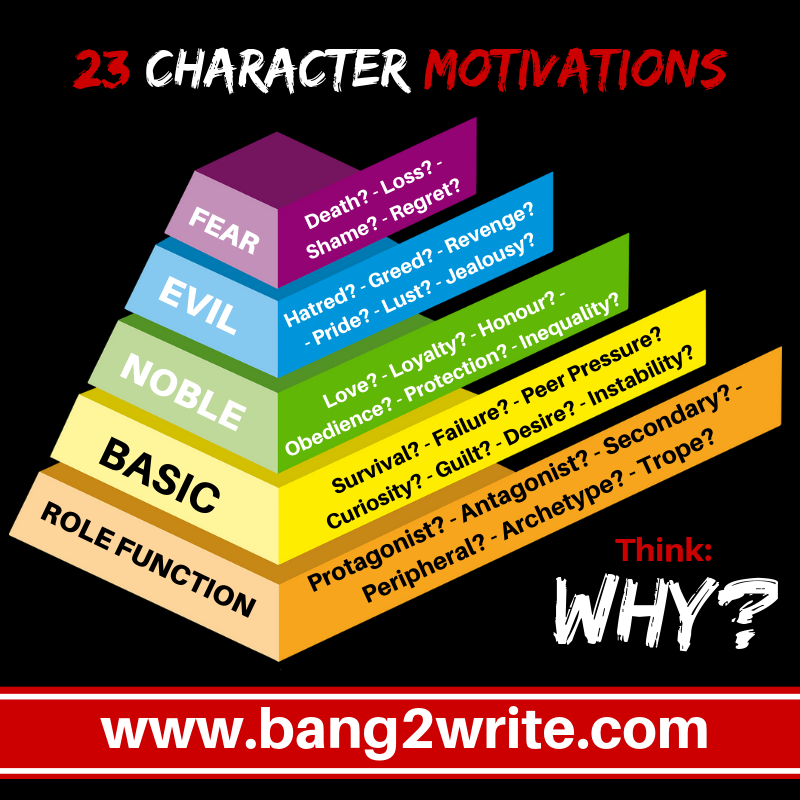

Explanatory material should:

- Be super-lean, as short as possible

- Not feel intrusive

- Weave into the narrative rather than interrupt it

- Create an emotional or visceral response if possible

- Occur during a natural pause or down-time in the narrative, not during high action or fast-moving dialog

- Never sound contrived

- Be written in the voice of the story’s narrator

Like active scenes, information should be told in a narrative voice, from your narrator’s point of view. Don’t switch to “documentary mode” in fiction, especially when you’re in-scene, or even between scenes. And one of the easiest ways to lose a reader is to interrupt active dialog with explanation. A common mistake is to have a character refer to something new in dialog and then spend a paragraph or two informing the reader about the background or why he said it. No! That is classic author intrusion. Characters don’t have time to think about that stuff while talking to each other.

An exception is purposefully using a device like separate chapters or scenes that temporarily distance the reader from the story line, such as snippets from newspaper articles or letters. It’s usually done in a different voice during the entire section, and it has to be done effectively. I’ve read good historical fiction with sections that use a wider-angle “camera” that pulls back from the individual characters for a time and gives an overview of what’s happening historically. It can’t last too long, and ultimately it has to circle back around and apply directly to the characters the reader cares about.

The bottom line is, data dumps interrupt the story, and anything that interrupts risks losing the reader. Readers identify with characters, not with information. The best way to give information is to weave it artfully into the narrative so the reader doesn’t notice it.