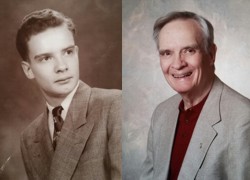

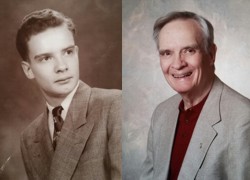

My dad, Bruce Keller, August 31, 1932 to March 29, 2017

Fathers are complicated, and none of them, at least the earthly ones, are perfect. They need a lot of grace, maybe more than the rest of us. What an overwhelming job they have, to carve out in young souls an image, an example, however blurred and sketchy, of what God our heavenly Father might be like.

My dad was a creative man with shimmering intelligence who could sit and chat for hours about cybernetics, geology, politics or astronomy. As he put it, he forgot birthdays and anniversaries, but he had perfect recall of interesting information he’d read in a book.

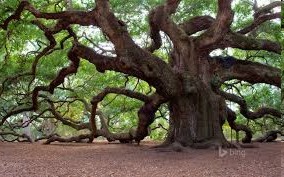

He was a dad who took us on hikes and searched for fossils, who talked our stuffed animals with distinctive character voices. He read us books at bedtime and took us to the library. Everywhere we went, he pointed out rocks and sedimentary strata around us and explained why they were twisted or bent or tipped up on edge. He gave us sharp-edged context for the physical world that surrounded us. Through my dad, I got a sense of the patience of geological time. And maybe the patience of God.

My dad was the first man I danced with, in the kitchen, my feet on top of his, the radio blaring some kind of swing-dance music. Dad taught me to drive on dusty back roads in upstate New York, attended my choir concerts and encouraged me to go to college. My life would have turned out very different without him. My sister, brother and I all learned word play from him, which continues on into his grandsons. He filled our lives with music and literature. This was never forced on us, but books were always stacked on end tables and the back of the toilet. I would often walk in for dinner and find him reading something to my mother while she cooked.

When Dad’s barbershop quartet wasn’t practicing in our living room, music always seemed to be playing in the background, from his own collection and from albums he brought home from the library. How many other kids my age could hum music by Ravel and Tchaikovsky, or knew the words to songs from musicals like “The Boys from Syracuse”? It’s from my dad that I developed my love for the English language—both reading it and writing it—for music, and for art. I knew that he loved me and never questioned that. He spent time with me, he talked with me, he joked around with me, he teased me, he treasured his grandchildren. He saved every letter I wrote him while I was learning how to be a mother and deal with children and adult life.

Dad had a wonderful sense of humor and a quick wit. He always managed to find the silliness or the absurdities in everyday life, and that humor remained intact up through the last months of his life. He approached his Parkinson’s disease and increasing physical limitations with curiosity, grace and humor. Even as his muscle control diminished, his wit and perseverance carried on. I’ve never seen anyone deal with their old age and infirmity with such philosophy, acceptance and lack of bitterness. He was not a complainer.

Everyone has a more difficult side, and parts of our lives that we regret. I won’t pretend my father was exempt from that. From my own experience, guilt can accumulate like a murky lake that never drains, like the Dead Sea. If it’s not addressed, it sits forever at the edge of our consciousness. We can pretend it’s not there. We can skirt it, maybe, hiding in the surrounding woods, trying not to look at it. Apologizing for all that stuff would require confronting the dead water, head-on, approaching it. We’re afraid if we get too close, it will suck at our toes and ankles. Maybe it’ll overwhelm us, and we’ll be drawn in and drown. So we hide around the edges and chase away anyone else who might get close enough to really look at it. That’s how I imagined it was for my dad. Between him and his first wife and his children he had gradually dug himself a dead lake of guilt and shame, and he lost track of how deep it went.

I was in my late twenties when I decided to forgive my father. Forgiveness comes when we decide that love wins. It doesn’t mean we never get mad again, or that we’ve forgotten things we can’t forget. It’s not flowers and bunnies and puppies. What it means is that love conquers anger and wins over our tightly held shield of self-righteousness. We let go of it and drop it.

To use another word picture, in my mind, it was like I pushed my boat out into those murky lake waters, my oars dipping into the shiny muck, the keel slicing through the oily surface. I saw it, I experienced it, I looked into it. I knew it was my father’s and not mine. I moved over the face of the brackish water to some symbolic floodgates, where I hammered open giant latches and swung out the great, rusty barriers. I could imagine the force of the water bursting and plunging over the edge, draining down the valley and soaking into the earth.

Too often we mistake that anger somehow protects us, when it really damages us. Holding grudges is painful and oppressive, and I wanted my dad to be free. As it turned out, though, the person set free was me. Forgiveness is funny that way.

Dad and I never talked much about it, I just walked about the last 30 years as if there were no dead lake between us. In my mind, there was nothing left but a dry depression filled with prairie grass and saplings. It was just an ancient lake bed now, layered with fossils and shale and all the twisted and stressed rock formations that formed that three-dimensional world my father had brought alive while I was growing up. Isn’t it strange how, like the landscape around us, all the stresses and pressures of life make it more beautiful and full of character? Layers of colorful sediment fused under great weight, rock metamorphosed by heat and pressure, mountains and staggering canyons and gorges built up and carved out by forces that seem, at first glance, destructive. This life is not a flat, barren land. It’s a string of national parks, and my father took me there.

Forgiveness and grace are simple, powerful forces. They remind us we’re all people, we are all mixed bags, and we’re all at fault. But we aren’t meant to carry our trash around forever. God has something better for us and wants to liberate us. It’s because of God’s forgiveness and grace that my father, for me, will continue to be the daddy who would turn up the radio in the kitchen and have me dance with him by putting my feet on top of his, dipping me backward until my hair swept the floor. And that is how I’ll remember him.

Just a little rant, which is always good for one’s system. The title subject occurs most often in American restaurants, specifically in establishments which send the manager, the chef, and—I think—the busboy out like robots to check and make sure everything was “excellent,” because I guess the server doesn’t believe us.

Just a little rant, which is always good for one’s system. The title subject occurs most often in American restaurants, specifically in establishments which send the manager, the chef, and—I think—the busboy out like robots to check and make sure everything was “excellent,” because I guess the server doesn’t believe us.