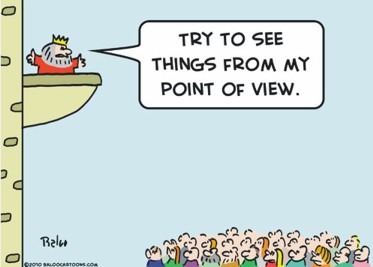

The second big topic we covered during writers’ workshop was point of view, a favorite agenda of David Coe’s. Everyone who has ever taken a writing course is probably aware of the basics of point of view: Your narrator can either speak in first person, third person limited, third person omniscient, or the always-irritating second person.

The second big topic we covered during writers’ workshop was point of view, a favorite agenda of David Coe’s. Everyone who has ever taken a writing course is probably aware of the basics of point of view: Your narrator can either speak in first person, third person limited, third person omniscient, or the always-irritating second person.

These days first person and third person limited are the points of view of choice for fiction. Third person omniscient (the narrator can be inside any character’s head at any given time) has gone out of style. Readers want to know which character to identify with, and an omniscient point of view makes them feel more distant and less connected. Writers can shift points of view in novels, but not mid-scene. We can only change after strong scene breaks or chapter breaks, and right out of the gate we have to make the point of view change clear to the reader.

In July’s workshop, though, we explored deeper into point of view, recognizing that we have to be careful only to include what our narrator/character could observe or know. Sometimes we think of storytelling the way it’s done in TV shows or movies, where multiple cameras record multiple points of view. Viewers don’t just observe the scene from the shoulder of the protagonist. Movies and TV are more omniscient in their storytelling than fiction, at least in observation. As a result of that influence, fiction writers can stumble into point of view violations without even realizing it.

For example, in a movie the camera can pull a tight close-up on the protagonist, sweating pores, messy hair and all. We get an immediate visual, by direct observation. But in fiction a first person or a third person limited character/narrator cannot describe himself using the same tools and methods we use to describe others. The writer can’t say, “I looked weary” or “his face went white” because the character can’t see his own face or countenance. (By the way, mirrors are a bad device to do that with.) The point of view character also cannot know what other characters are feeling or thinking. She can only assume, in the same way in real life we try to interpret others’ feelings by observing their mannerisms or facial expressions.

But there are other, more subtle, point of view violations. One of mine was my protagonist Paul observing specifically what his girlfriend was looking at during dinner. Because Paul was sitting right next to her, shoulder to shoulder, he probably couldn’t see exactly where her eyes were resting, he could only maybe judge the general angle of her gaze and hazard a guess. Another issue was he wouldn’t be able to see what his own rear tires were kicking up while driving, only what was spraying up from the cars in front of him. So we writers need to inhabit the character whose point of view reigns in the scene. What could the character actually know? What would he see and experience?

Readers can sense when you’ve hit a point of view violation (“Wait… how could this character know that?”), and it brings them out of the story. We never want to do that. We want them so engaged in the story that they don’t want to put the book down!