Other than an almost-but-not-quite-finished adventure I wrote when I was thirteen, I had never written a full-length book before this past year. That adolescent adventure story was about a young boy from Canada who owned sled dogs. I knew very little about Canada or sled dogs, and even less about boys. I wish I still had that manuscript. I’m curious to see if I had any sense of story structure back then.

Other than an almost-but-not-quite-finished adventure I wrote when I was thirteen, I had never written a full-length book before this past year. That adolescent adventure story was about a young boy from Canada who owned sled dogs. I knew very little about Canada or sled dogs, and even less about boys. I wish I still had that manuscript. I’m curious to see if I had any sense of story structure back then.

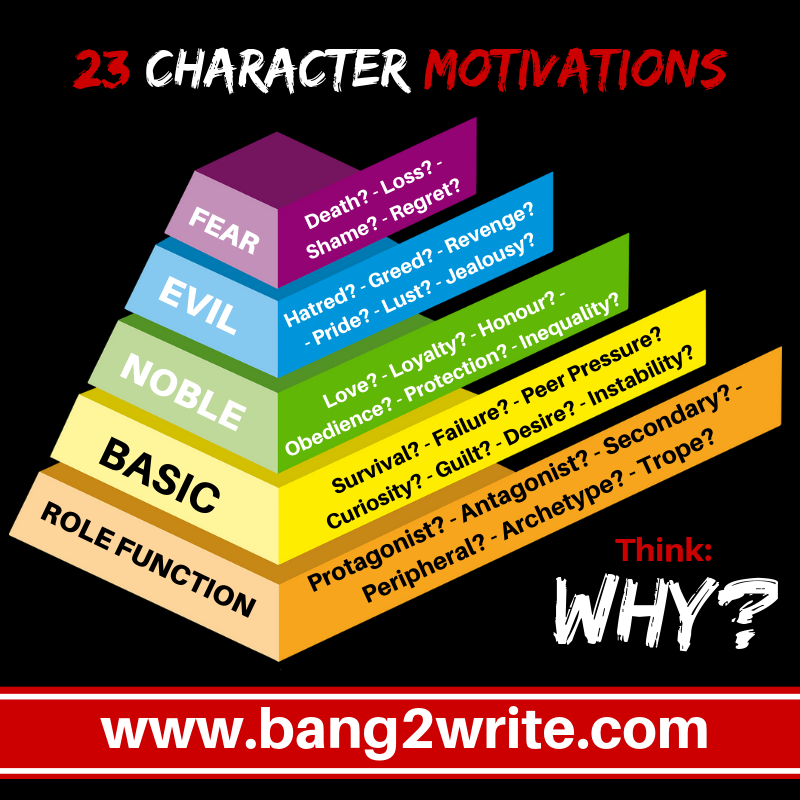

In my next blog I’ll talk about how I got started with the writing itself, but here I wanted to address story structure. Story structure is basically the plot, but it’s a strategic approach to steering or mapping out the plot. A good novel or memoir has to have wonderful characters and terrific writing, but if the plot falls on its face, the reader will be disappointed.

I wrote a lot of poetry and short stories throughout college and my twenties, and two of the short stories were published. I also got a short, one-act play published. But plot is not as important in a shorter piece of writing. You’re dipping into a character’s life for a limited time, and in literary writing it’s more about what’s happening internally to characters. A full-length book was a different kind of project. It would take some planning. I’m not a natural planner. I hate outlines. For me the joy of writing is watching the story and characters unfold organically.

This project taught me that human beings have a built-in sense of story structure. We have it when we read a novel or watch a movie or when we share ghost stories around a campfire. We think of stories in three acts. There’s a beginning, with set-up of characters and conflict and a clarification of the stakes, a middle where conflict is fully engaged and the hero or heroine is stretched to the limit and has to make some decisions, and the ending, where the main character(s) has grown or changed and things are resolved one way or another. Preschoolers can set up a three-act story structure without even thinking about it. 1) There was a guy with a horse. 2) One day a bad guy tried to steal his horse. 3) The hero shot the bad guy and rode off into the sunset.

When I first began my book, I approached it like writing a short story. I knew all about conflict from high school English, and was aware of character development and good writing from my bachelor’s education and years of writing. Adverbs are bad, strong verbs are good, etc. But I wasn’t thinking about structure, I was thinking more about characters; after all, memoir is by nature character-driven. I began writing a bunch of memory vignettes and scenes and then later realized I wasn’t sure how to put them all together. This wasn’t a collection of short stories, it needed to be a cohesive, longer story. The main character needed a goal to pursue, heavy opposition to achieving that goal, and a way to meet the opposition and resolve things.

What I did find out was that unexpected themes can emerge as you write. This was the joyful part. I kept stumbling over one particular theme that finally became what my narrator was seeking in my book (and what I was seeking as a person). It helped define the stakes and made sense of the conflict. And, since it’s a memoir, these surprise themes helped make sense of my life story.

Naturally I read a lot of good memoirs over the past year (I’ll list some later), but I also began reading books on story structure. Structure is something that isn’t taught, at least in undergraduate writing programs. My cousin has an MFA in writing and tells me it isn’t covered there either. Larry Brooks wrote a book titled Story Engineering. In it he uses lots of technical terms like plot points and pivot points, and he is a staunch believer in outlining. He gives lots of good info. But I took one look at his multipage template outline and nearly passed out. It felt too much like a college theme paper project. Then I picked up another book, Plot and Structure by James Scott Bell. He devoted part of that book to NOPs (no-outline people) and explained that even those writers at some point have to exert structure on their stream-of-consciousness writing. But he took the sting out of writing to a detailed outline and addressed structure from a more strategic viewpoint, which was helpful for me.

So I kept writing and editing and rewriting. Eventually I split everything I’d written into scenes or chapters and wrote a quick blurb about each one on index cards. Then I laid them all out on the floor and moved stuff around and suddenly began to discern some natural structure. I saw where I needed stronger transitions. I also used this technique to balance the story and make sure all the climactic scenes didn’t happen at once. I was able to build tension at a reasonable pace, giving the reader some time to recover from the most intense scenes. I was able to take out scenes or paragraphs that weren’t necessary. It was a great exercise.

Bottom line: You can’t write a full-length book without at some point thinking about story structure.