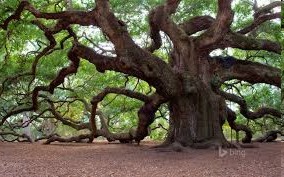

Riding my horse this past weekend through our wooded trails, I was struck by how immersed I was in my surroundings. Not just with my tactile, visual, auditory and aromatic senses, but the feeling of being in the woods in spring. In April the tall weeds haven’t taken over yet, and wild flowers are everywhere, carpeting the clearings and lanes: buttercups, marsh marigolds, violets, Dutchman’s breeches (isn’t that a wonderful name?) and grape hyacinth. The river snakes alongside the trails, reflecting purples and yellows. And exposed are gnarled fallen logs, huddled in cloaks of moss, poking up like knees and elbows from the low greenery.

Riding my horse this past weekend through our wooded trails, I was struck by how immersed I was in my surroundings. Not just with my tactile, visual, auditory and aromatic senses, but the feeling of being in the woods in spring. In April the tall weeds haven’t taken over yet, and wild flowers are everywhere, carpeting the clearings and lanes: buttercups, marsh marigolds, violets, Dutchman’s breeches (isn’t that a wonderful name?) and grape hyacinth. The river snakes alongside the trails, reflecting purples and yellows. And exposed are gnarled fallen logs, huddled in cloaks of moss, poking up like knees and elbows from the low greenery.

In writing about a particular setting, we know how important it can be to get the “essence” of a place. This enhances the story and can reveal a lot about how characters are feeling, without telling or summarizing. If they’re depressed, they’ll view their environment one way, and another way if they’re feeling good. Or maybe their environment changes the way they feel. In some books and especially for certain genres that require world-building, setting is so important it’s almost a “character” in the story. Even in literary fiction, this can be true; I immediately think of Housekeeping by Marilyn Robinson. Her descriptions of Idaho mountains and the lake are haunting. Like her, we can also use setting to expose themes.

This doesn’t mean we start each scene with a long description of the setting, because that’s not action, conflict or character, and it can get boring and lose the reader. But if we build the feel of the setting as we go, throwing in little glimpses and sensory details—not all the details, just the right details—as the story moves along, a complete setting takes shape like magic in the reader’s mind. If we do it right, the reader will feel immersed, transported into another world. Setting can evoke tension, suspense, depression, fear, joy, exhilaration… all those things we love to evoke in readers. We can use setting and a character’s response to it instead of saying, “John felt melancholy.”

While in the saddle, I spent time just wandering the woods, immersing myself in it, breathing it in, watching how the shadows played across the forest floor, observing the contours of fallen walnuts and limbs and the way a red squirrel launched itself fifteen feet from the ground into a tree. I thought to myself, how would I describe this? What unique similes and metaphors would work? What strong verb would absolutely nail this?

Good authors of historical fiction, for example, don’t just sit in a library or in front of a computer and do their research. They visit the locations they plan to write about. They walk the ramparts, hike the old Roman roads, spend a night or two in the Arabian Desert, ride an elephant in India. An old saying goes, “Write what you know.” To do that, we have to know and experience our world, so we can borrow from our memories and impressions. We need to sit and meditate in locations, pay attention to how they make us feel, and then use that to the fullest when we create setting.