Today I plan to ramble on about malaprops and mixed metaphors, partly because I’m in a silly mood. Malaprops are words or phrases that sound similar to something coherent, but don’t have the meaning intended. They are mistakes to avoid in writing (unless it makes for funny dialog), but they can also be funnier than a long-tailed cat in a room full of rocking chairs. Mixed metaphors use pieces from two or more familiar clichés.

Today I plan to ramble on about malaprops and mixed metaphors, partly because I’m in a silly mood. Malaprops are words or phrases that sound similar to something coherent, but don’t have the meaning intended. They are mistakes to avoid in writing (unless it makes for funny dialog), but they can also be funnier than a long-tailed cat in a room full of rocking chairs. Mixed metaphors use pieces from two or more familiar clichés.

My mother, who passed away in 2009, was the queen of mixed metaphors. My all-time favorite of hers was: “We’ll burn that bridge when we come to it.”

I once used this wonderful phrase at work, and it caught on like wildfire through tumbleweed. Now it’s used regularly in meetings, and I have the satisfying assurance that someone will use it at a get-together, forgetting that it’s not quite the right cliché.

At work we also used a malaprop, which might be from Groucho Marx; at least it sure sounds like him. But it’s great when you really have nothing good to say about someone: “Of all the people I’ve ever met, you are certainly one of them.” People generally react with a slight frown and say, “Thank… you…” because they can’t quite put their finger on what wasn’t right.

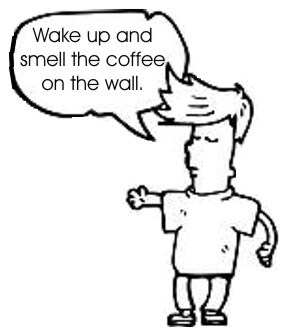

One of my mother’s great malaprops was “very close veins,” which arguably describes them. But she mostly mixed metaphors, interchanging pieces and parts like Tinkertoys. Sometimes it wasn’t the zany mixture she came up with that was funny, but the leftovers. She once said, “It’s as plain as the handwriting on the wall,” which doesn’t sound too bad. But my father immediately pointed out the leftovers: “I can see the nose on your face.” And that had us rolling on the floor.

My husband came out with a weird mixed metaphor once, talking about a crazed motorist he’d encountered on the highway: “He was driving from the hip.” That was baffling enough, but I had to point out the leftovers: “He was shooting by the seat of his pants.” Now we’ve got something!

Yogi Berra was probably the king of malaprops and mixed-up metaphors, but here are a few other great ones I ran across while researching this fascinating and time-gobbling topic (most borrowed from www.jimcarlton.com):

- “We could stand here and talk until the cows turn blue.”

- “He’s a wolf in cheap clothing.”

- “I wouldn’t eat that with a ten-foot pole.”

- “He’s not the one with his ass in a noose.”

- “From now on, I’m watching everything you do with a fine-toothed comb.”

- “These hemorrhoids are a real pain in the neck.”

- “He’s burning the midnight oil from both ends.”

- “People are dying like hotcakes.”

- “We have to get all our ducks on the same page.”

- “She’s suffering from a deviated rectum.”

Aside from blasting our drinks out of our noses when we read these, we writers need to pay attention to our own metaphors and make sure they make sense. Clichés are bad enough in their own right, but if we mix them together our readers will wonder what on earth is going on. Even when we write something unique, we need to be accurate in our analogies. Here are some funny, not-so-successful analogies written by high school students:

- “Her face was a perfect oval, like a circle that had its two sides gently compressed by a Thigh Master.”

- “The little boat gently drifted across the pond exactly the way a bowling ball wouldn’t.”

- “Her hair glistened in the rain like nose hair after a sneeze.”

And now for an analogy that really works, written by Pulitzer Prize winner Marilynne Robinson in her novel Housekeeping:

“…the engine nosed over toward the lake and then the rest of the train slid after it into the water like a weasel sliding off a rock.”

May your own sparkling metaphors come to you as easy as falling off a piece of cake.